Specialist Drug Lawyers

Defending Drug Cases is All We Do

Experienced in Drug Cases

Thousands of Satisfied Clients

Outstanding Track Record

Exceptional Results in Drug Cases

Defending Drug Cases is All We Do

Thousands of Satisfied Clients

Exceptional Results in Drug Cases

In Downing Centre District Court, Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained a ‘Section 10’ (no conviction) for a 22 year old Carramar man who pleaded ‘guilty’ to possessing 7 ecstacy tablets at Sydney’s ‘Future Music Festival’.

The Presiding Judge was persuaded to allow the man to remain ‘conviction free’ as any conviction may have resulted in him losing his job.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® convinced the Presiding Magistrate in Downing Centre Local Court not to record a conviction against a 33 year old St Leonards man who pleaded ‘guilty’ to possessing 5 ecstacy pills, despite him already having a ‘Section 10’ in 2004 and a criminal conviction in 2006.

Our client attended counselling, wrote a ‘letter of apology’ and obtained references in the lead-up to his case, and submissions were made to the Magistrate about the effect of a ‘drug conviction’ on his job prospects.

After convincing the DPP to drop charges of ‘drug supply’ and ‘good in custody’, Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained a ‘Section 10’ (no criminal conviction) for our 20 year old Artarmon client who then pleaded guilty to a single charge of ‘possessing’ an indictable quantity of ecstacy tablets.

He is studying Civil Engineering and a criminal record may have impacted upon his future job prospects.

Drug Supply & Drug Possession charges were Dismissed in Downing Centre Court after the Magistrate found there was insufficient evidence to prove that our 22 year old client supplied or possessed drugs.

Police officers gave evidence in court that they were certain our client threw 2 bags of cocaine into a bush as they approached him with a sniffer dog.

Our client denied the allegation and the Magistrate found that another person may have possessed and discarded the drugs.

After having a charge of ‘deemed supply’ withdrawn, Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained ‘Section 10s’ (no convictions) for our 51 year old client who then pleaded guilty in Downing Centre Local Court to possessing 12 ‘Ecstacy’ Tablets and a quantity of Ketamine.

Our client had no previous criminal convictions.

No conviction was imposed upon our 23 year old Clovelly client for possessing 4 tablets of ‘Ecstacy’ and 9 tablets of ‘Amphetamines’.

He was initially charged with ‘drug supply’ due to the number of pills, but Sydney Criminal Lawyers® had the supply charge withdrawn and replaced with ‘possession’ charges.

He then pleaded ‘guilty’ to possession and was dealt with under ‘section 10’ (no criminal conviction).

He is undertaking the final year of his law degree and had completed the MERIT Drug Program in the lead-up to his sentencing.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained ‘suspended sentences’ in Downing Centre District Court for our 27 year client who was caught under surveillance supplying 1000 ecstasy tablets and 79 grams of ‘ice’, and pleaded guilty.

The exceptional result was achieved by initially convincing the court to grant a lengthy adjournment – which is called a ‘section 11 bond’.

This allowed our client to complete 9 months of rehabilitation at Odyssey House.

He then started teaching others at that rehabilitation centre and continued his outpatient treatment.

Our client has come a very long way towards overcoming his underlying drug addiction and intends to eventually start his own landscaping business.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained bail in Central Local Court for a 26 year old man charged with having 4.75kg of imported Cocaine, which is an offence carrying a maximum penalty of life imprisonment and a ‘presumption against bail’.

In Parramatta District Court, Sydney Criminal Lawyers® had all charges dismissed against a 26 year old man accused of supplying ‘ice’ and ‘ecstacy’ on an ‘ongoing basis’.

This result was obtained despite there being police surveillance and telephone intercepts allegedly establishing that our client supplied the drugs on at least 12 occasions over nearly 6 weeks.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained a ‘Section 10’ (ie no criminal conviction) for a 30 year old man after persuading police to reduce a charge of ‘supply prohibited drug’ to ‘possess prohibited drug’ and then convincing the Magistrate that a criminal conviction would impact negatively on his employment prospects.

In Parramatta Court, Sydney Criminal Lawyers® had all drug charges dismissed for a 26 year old man found with ‘ecstacy tablets’ and ‘ice’ in his bedroom draw, on the basis that police could not prove ‘exclusive possession’.

Police were then ordered to pay our client’s legal costs because they failed to properly investigate the possibility that the drugs may have belonged to his girlfriend, who was staying in the same room at the time.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® had all drug supply and possession charges dismissed in Downing Centre Court by arguing that the police search of our client’s car was illegal.

Our client was driving his vehicle in Ultimo when police pulled him over for a random breath test.

Police claimed that while approaching the car, they observed our client lean over in a manner consistent with placing an item underneath the passenger seat.

They asked him “what did you just put under the seat” to which he replied “nothing”. Police administered a breath test which came back negative.

Police then advised they suspected our client of being in possession of drugs. They searched the car and located a small resealable bag containing 12 ‘ecstacy’ pills under the passenger seat.

They charged him with drug supply (deemed) due to the number of pills found and also with drug possession.

During the hearing, it was argued that simply observing a person lean over is insufficient by itself for police to form a reasonable suspicion in order to search the car. Indeed under cross examination during a voire dire (a hearing within a hearing), the officers admitted not being able to see any item in our client’s hand but simply seeing him momentarily lean over. It was also established the officers could not have had a clear view of this from their position.

The magistrate accepted that argument and found the ensuing search was illegal. She applied section 138 of the Evidence Act to exclude the evidence of drugs found after the search, and dismissed both charges.

The case serves as a reminder that a ‘reasonable suspicion’ must be ‘more than a mere possibility’ and based upon solid grounds; as per the leading case of R v Rondo.

Our clients (two men and a woman) were travelling to the ConFest Festival in the ACT when their car was stopped and searched by police.

Police found 5.5g of liquid LSD, 1 sugar cube of LSD, 4 MDMA/ecstasy pills and 2 grams of cannabis after a drug detection dog alerted them to the presence of drugs within the vehicle.

When questioned by police, our clients said that the drugs were for personal use only. Consequently, two of our clients were charged with two counts of ‘drug possession’ for the LSD and MDMA, while the third was charged with ‘possession of cannabis.’

They were represented by another law firm in the Local Court, where they were convicted of all charges and received heavy fines.

Unhappy with this result, they then contacted Sydney Drug Lawyers and explained their case to Mitchell Cavanagh, one of our expert senior drug defence lawyers.

Mr Cavanagh lodged an appeal against their sentence in the District Court, arguing that it was too harsh. He subsequently obtained ‘section 10s’ for each of our clients – meaning that they did not receive convictions on their criminal records and avoided the heavy fines originally imposed by the Local Court.

Mr Cavanagh was able to obtain this outstanding result by presenting evidence in court to show that ‘section 10s’ are able to be awarded even in serious drug cases which involve large quantities of different drugs and numerous charges.

Thanks to Mr Cavanagh’s expert knowledge of drug law and his excellent advocacy skills, our clients were able to get on with their lives without worrying about the impact of a criminal record.

This case shows how valuable it can be to have a specialist drug lawyer on your side – our in-depth knowledge of drug law, coupled with our experience defending these types of cases allows us to obtain excellent results when other law firms are unable to do so.

Our client was a 24 year old woman who attended the Stereosonic Music Festival in Sydney. She was charged with two counts of ‘drug possession’ and one count of ‘drug supply’ after police allegedly saw her selling ecstasy pills at the festival.

After searching her, police found 16 ecstasy pills which weighed 5.44 grams in total, as well as a capsule containing amphetamines.

Due to the large quantity of drugs, the matter had to be heard in the District Court.

Despite the prosecution having a strong case for ‘actual supply,’ our expert criminal lawyers were able to persuade the prosecution to amend the facts so that she was charged with ‘deemed supply,’ which is a much less serious charge that carries lesser penalties.

Our client then pleaded guilty to one count of deemed supply.

Sydney Drug Lawyers then put our client in the best possible position before her sentencing date by helping her collect character references and encouraging her to attend counselling.

We then worked hard to persuade the court to deal with the matter by way of a ‘section 10,’ which meant that our client avoided having a conviction recorded on her criminal history and did not have to pay heavy fines.

Our client was then able to continue her job as a Project Analyst without worrying about how a criminal record could affect her job.

This was an excellent result given the seriousness of the charges and the large amount of drugs involved. Again, it demonstrates how valuable it is to have a specialist drug lawyer on your side who will ensure that you get the best possible result in your drug case.

Our client was a 42 year old man who was charged with drug supply.

Police alleged that he was part of a criminal syndicate that was involved in supplying heroin and ecstasy.

They began a surveillance operation in May 2013 and obtained evidence including phone intercepts and video surveillance which showed that our client sold drugs on behalf of others who were higher up in the syndicate.

Our client, along with two others allegedly involved in the syndicate, was charged with numerous drug offences including ‘drug supply’ for heroin.

Despite the strong evidence obtained by police and the seriousness of the charges, our expert defence team fought hard to have the charges dropped on the basis that there was not enough evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that our client committed the offences.

As the charges were dropped before the matter went to court, our client was also able to avoid the time and expense involved in a District Court trial.

He is now able to move on with his life without a conviction on his criminal record, which could have seriously impacted his ability to work and travel.

The other two persons who were charged with drug offences chose to be represented by another ‘general’ criminal law firm that was unable to have the charges dropped. As a result, they now face the stress and expense of a District Court trial.

This goes to show that the knowledge and experience of a specialist drug lawyer can make all the difference when it comes to getting an outstanding result in your drug case.

Our client was a 30 year old Italian male who was observed selling capsules at the AVICII concert in Centennial Parklands.

He was searched by police who found 73 capsules and pills believed to be ecstasy in separate bags, as well as $770 cash.

Police arrested him and charged him with ‘drug supply’ and ‘dealing with the proceeds of crime.’

However, the substances were later analysed and determined to be a legal drug known as ‘Lofton,’ rather than ecstasy.

Our senior defence team was able to fight to have the charges dropped even though the law says that you can still be charged with drug supply if the pills simply resemble drugs and are sold under the assumption that they are illegal drugs.

However, our specialist lawyers argued that there was not enough evidence to show that our client was selling the substances as illegal drugs.

As a result, the prosecution dropped the charges at an early stage, and our client was able to avoid a lengthy and costly trial, as well as heavy penalties.

This is yet another example of an excellent result obtained thanks to the hard work and in-depth knowledge of our specialist drug defence lawyers.

Our client was a 24 year old male who was approached by police in a nightclub after reports that he was selling ecstasy.

Police spoke to the man and asked whether he had any drugs on him, and he immediately showed them a small plastic bag containing 8 ecstasy pills.

As a result, he was charged with ‘drug possession’ and ‘deemed drug supply.’

‘Deemed supply’ is a unique charge that applies in situations where you have a certain amount of drugs upon you and it is automatically presumed that you intended to sell them.

You can be charged with ‘deemed supply’ even if there is no other evidence to suggest that you intended to sell the drugs to other people.

Despite the seriousness of these charges and the amount of drugs involved, our expert defence team was able to persuade the prosecution to drop the ‘deemed supply’ charge.

Our client then pleaded guilty to the ‘drug possession’ charge, however his senior defence lawyer, Mr Nedim, was able to obtain a section 10.

A ‘section 10’ is where you are found guilty of the charges but no conviction is recorded on your criminal record.

Sometimes, having a criminal record can affect your ability to find a job or travel overseas. In this case, our client was studying accounting and was worried about how a criminal record would affect his ability to find a job after university.

Thanks to the effort and hard work of our expert defence lawyers, he is now able to move on with his life and pursue his chosen career path.

Again, this excellent result shows how you can benefit from the knowledge and experience of a specialist drug lawyer.

Our 29 year old client was pulled over by police, who alleged that he was speeding and driving recklessly.

When speaking to police, they claimed that he appeared nervous and fidgety and was sweating profusely.

Police then conducted a background check and found that our client had a previous drug conviction. On this basis, they searched his car and found 58 grams of cannabis. He was then charged with ‘drug possession’.

However, our expert defence team argued that having a previous drug conviction is not enough to justify a search, and that our client’s nervousness was normal in the circumstances.

The Magistrate accepted these arguments and found that the police had searched our client’s car illegally. The evidence of drugs was then able to be excluded on this basis and the case was dismissed.

This shows how valuable it can be to have a specialist drug defence lawyer on your side with an expert knowledge and understanding of drug law.

Our client was a 37 year old male who was charged with a variety of offences, including ‘cultivating a prohibited plant for commercial purposes‘ for growing 14 large cannabis plants in his Camperdown apartment.

He came to us after two other law firms told him that he would likely face 15 months to 2 years in prison.

He was also told that due to the seriousness of the charges, he would not be able to participate in the MERIT program, and the matter would have to be dealt with in the District Court.

However, with the help of the experts at Sydney Drug Lawyers, he was able to have the charges downgraded to ‘cultivation’ and ‘possession’ for personal purposes only. This meant that the case stayed in the Local Court, where the penalties are much lower.

Our client was also able to undertake the MERIT Program and ended up with a section 9 good behaviour bond, as well as a number of small fines – a great result considering other law firms had advised him that he was facing gaol time.

The specialist drug lawyers at Sydney Drug Lawyers frequently obtain excellent results in complex cases where other lawyers have given up hope.

Our 27 year old client was charged with commercial drug supply after being caught on surveillance supplying 1000 ecstasy pills and 79 grams of ice.

He pleaded guilty to the charges, however our expert defence lawyers were able to persuade the court to issue him with a ‘section 11 bond.’

A section 11 bond allows the matter to be adjourned to allow you to complete rehabilitation. The court will then determine your sentence after you finish the rehabilitation or intervention program.

Our client used this time to undergo a 9 month rehabilitation program at Odyssey House. During this time, he made significant progress in addressing his drug problems and eventually began teaching other people at the rehabilitation centre.

When it came to sentencing, our expert defence lawyers highlighted his outstanding efforts in rehabilitation and fought hard to obtain a suspended sentence for his offences.

This is a fantastic result given the serious nature of the charges. Thanks to the efforts of our senior defence team, our client has been able to continue his outpatient treatment and plans to start his own landscaping business.

Our 20 year old client was charged with two counts of ‘drug supply’ and one count of ‘drug possession.’

Our experienced criminal lawyers worked tirelessly to get the drug supply charges dropped outside of court. We then fought hard to obtain a ‘section 10’ for the drug possession charge.

A ‘section 10’ is where you are found guilty of the charge, but no conviction is recorded on your criminal record. This is a best-case scenario outcome, as a criminal record can make it difficult to find work or travel overseas.

The experts at Sydney Drug Lawyers are frequently successful in obtaining ‘section 10s,’ even in more serious drug cases such as ‘drug supply.’

Because of this excellent result, our client is now able to move on with her life and pursue her career as a social worker.

Our 22 year old client came to us worried about the prospect of going to gaol after he was charged with supplying 60 ounces of heroin and cocaine over a period of several months.

He was charged with multiple offences including ‘supply drugs on an ongoing basis,’ ‘participate in criminal group’ and 11 counts of ‘supply prohibited drug.’

These offences are treated seriously by the courts and generally result in a prison sentence – indeed, our client had fully expected to go to gaol.

However, our highly-experienced principal, Ugur Nedim, was able to put forth compelling arguments which persuaded the Judge to deal with the matter by way of a suspended sentence.

A suspended sentence is an alternative to full-time gaol. It is a good behaviour bond which enables you to go about your daily life provided that you stick to the terms and conditions of the bond.

This meant that our client did not end up in prison, despite the fact that he had prior convictions – an outstanding result considering statistics for these offences showed that 100% of offenders went to prison.

Our client was a 23 year old male who was in his final year of law school.

He was caught with 4 pills containing ecstasy and 9 pills containing amphetamines.

Due to the large number of pills, our client was charged with ‘drug supply.’ However, our lawyers fought to have the supply charge reduced to a ‘drug possession’ charge, which carries much lesser penalties.

Our lawyers then encouraged him to participate in the MERIT Drug Program prior to his sentencing, which he completed with great success.

When it came to his sentencing, our expert lawyers highlighted his outstanding participation in the MERIT Program as well as his prior good character, and were able to obtain a ‘section 10.’

This meant that no convictions were recorded on his criminal record, and he was able to pursue his career as a lawyer.

Again, it just goes to show that having a specialist drug lawyer on your side can give you the best possible advantage when it comes to fighting the charges.

Our client was a 51 year old male who was charged with ‘deemed supply’ after he was found with 12 ecstasy pills and a quantity of ketamine.

Our skilled lawyers worked hard to have his deemed supply charge downgraded to ‘drug possession.’

Our lawyers were able to obtain a ‘section 10’ by drawing attention to his clean criminal record and his prior good character.

This shows how valuable a specialist drug lawyer can be when it comes to securing a positive outcome in your drug case.

Police charged our 22 year old client with ‘drug supply’ and ‘drug possession.’

They alleged that he threw 2 bags of cocaine into the bushes when he was approached by police and a sniffer dog.

Our client pleaded ‘not guilty’ to the charges, and with the help of our experienced criminal defence team, he was able to convince the Magistrate that someone else may have thrown the drugs into the bushes.

As a result, all charges were dismissed and our client was found ‘not guilty.’

This excellent result was obtained because of the expert knowledge and skills of our highly experienced specialist drug lawyers.

Our 20 year old client was charged with ‘drug supply’ and ‘goods in custody.’

However, thanks to the hard work of our specialist drug lawyers, we were able to convince the DPP to drop these charges.

Instead, our client pleaded guilty to a single count of ‘possessing an indictable quantity of ecstasy pills.’

Our lawyers then fought hard to present his case in the most positive light, and were able to secure a ‘section 10,’ which is where you are found guilty but no conviction is recorded on your criminal history.

This meant that our client was free to pursue his career as an engineer – ordinarily, had a conviction been recorded, he may have faced difficulties in applying for jobs.

This is yet another wonderful result obtained thanks to the skills of our highly-respected drug lawyers.

Our client was a 33 year old male who was charged with ‘drug possession’ after he was found with 5 ecstasy pills.

He had previously had a criminal conviction in 2006, as well as a ‘section 10’ in 2004.

Our expert defence team encouraged our client to attend counseling, write a letter of apology, and obtain character references from his employer.

At sentencing, our expert lawyers drew attention to the positive steps our client had taken in getting counselling and demonstrating remorse in his letter of apology.

We also highlighted the impact that a drug conviction would have on his career and future.

Thanks to these compelling arguments, our lawyers were able to convince the Magistrate to issue a ‘section 10,’ which is where no conviction is recorded.

This was a fantastic result, especially since our client had a previous criminal record and had already obtained a section 10 in the past.

Our 26 year old male client was charged with ‘drug possession’ after police found ecstasy pills and ice in his bedroom drawer.

However, our highly experienced lawyers argued that there was a possibility that the drugs belonged to our client’s girlfriend.

Accordingly, police were unable to prove ‘exclusive possession’ – in other words, the police were unable to prove that the drugs belonged only to our client.

We were also able to get the police to pay for our client’s legal fees as they should have investigated the possibility that the drugs belonged to our client’s girlfriend.

This was a great outcome as our client escaped conviction and was able to get on with his life without having to worry about paying for his legal expenses.

It just goes to show that sometimes, having a knowledgeable specialist drug lawyer on your side pays for itself!

Our 30 year old client was charged with supplying a prohibited drug.

Our lawyers were able to convince police to downgrade this to a ‘drug possession’ charge, to which our client pleaded guilty.

Our highly-experienced advocates then stressed the negative impact that a conviction would have upon our client’s employment prospects, and accordingly the Magistrate was persuaded to issue a ‘section 10.’

This meant that our client did not receive a conviction on his criminal record and was free to pursue his chosen career.

Our client benefited from the experience of our specialist drug defence team, and was able to obtain the best possible result in his case.

Our 26 year old client was charged with supplying ice and ecstasy on an ongoing basis.

Prosecution evidence against our client was strong and included police surveillance of our client as well as telephone intercepts which allegedly showed that our client supplied drugs.

However, our dedicated and experienced lawyers were able to convince the District Court Judge to dismiss all charges – meaning that our client was found ‘not guilty.’

He is now able to get on with his life without being marred by a criminal conviction.

Our 26 year old client was charged with possessing 4.75kg of imported cocaine.

The large amount of this drug attracts extremely heavy penalties, including life imprisonment.

Our client also had a prior conviction for drug supply in the USA and was not an Australian citizen, nor did he have links to the Australian community.

Despite these unfavourable circumstances, the specialist defence team from Sydney Drug Lawyers was able to get our client bail.

This was a fantastic result given the seriousness of the charges and shows that it pays to have the experts on your side.

Our expert drug lawyers recently represented a client who was charged with driving under the influence of a prohibited drug (DUI).

He was pulled over by police after it was alleged that he was veering between lanes without indicating.

Police then alleged that they smelt cannabis inside the vehicle when speaking to our client.

When asked about the smell, our client admitted that he had smoked cannabis prior to being pulled over by police.

He also handed over a joint that was inside the car.

Police conveyed out client to hospital where blood and urine samples were taken from him. The samples revealed that our client had high concentrations of THC in his blood and urine.

In court, our highly experienced drug lawyers argued that our client suffered from various medical problems, such as severe hernia pain.

It was argued that if his licence were disqualified, our client would be unable to attend medical appointments, and further, catching public transport would be difficult due to the severity of the pain suffered.

Our lawyers also argued that our client used cannabis as a form of pain relief, rather than for recreational purposes.

Despite the strength of the case against our client, as well as his lengthy driving record, our drug law specialists were able to persuade the magistrate to impose a ‘section 10.’

This means that while our client was found guilty of the offence, the charges will be not recorded on his criminal record.

It also means that he avoids having his licence disqualified.

This fantastic outcome means that our client is able to continue working and travelling without the charges severely impacting his life.

Our drug lawyers regularly represent clients in DUI cases and have a proven track record of obtaining excellent results such as ‘section 10s.’

The annual Harbourlife Music Festival was held on the 8th of November this year.

Three of our clients were charged with drug possession after police found various types of drugs upon them, including 7 ecstasy pills, marijuana, cocaine and ice.

Thankfully, our highly experienced senior drug lawyers took the time to carefully prepare ‘sentencing submissions’ which emphasised the need for a lenient penalty.

As a result of the hard work and dedication of our expert lawyers, all of our clients walked away with ‘section 10s.’

A ‘section 10’ is where you are found guilty of an offence, but no conviction is recorded on your criminal record.

This means that each of our clients is able to get on with their lives without worrying about how a criminal conviction could affect their employment or travel plans.

Our lawyers frequently obtain ‘section 10s’ in drug possession and supply cases.

These phenomenal results highlight the value of having an experienced drug law specialist on your side.

Our drug law specialists recently represented a 26-year-old Columbian man who was alleged to have imported 63 kilograms of methamphetamine into Australia from South America.

He was charged with commercial drug importation under the Commonwealth Criminal Code.

The maximum penalty for this offence is life imprisonment.

Despite a strong prosecution case and the seriousness of the charges, our experienced drug lawyers were able to persuade the magistrate to grant our client bail.

This means that our client is able to remain at liberty in the community until his matter is heard in court.

We were able to achieve this desirable outcome thanks to the efforts of our dedicated drug law experts, who spent a considerable amount of time preparing written submissions to the court which emphasised factors such as delays with the prosecution serving evidence, the length of time that our client would spend in prison before his trial, and his need to be free to assist in preparing his case.

This fantastic result means that our lawyers can now work with our clients to secure the best possible outcome in his case.

There have been significant amendments to the Bail Act in recent times, and it certainly pays to have a lawyer on your side who is familiar with these changes.

Our senior lawyers regularly prepare bail applications in the Local, District and Supreme courts and have an expert understanding of bail laws.

Our expert knowledge and experience is reflected in our ability to obtain bail for our clients in even the most serious drug cases, such as this one.

Our expert defence team recently represented nine clients who were charged with drug possession at Stereosonic 2014.

Our clients came from all walks of life and held jobs in various fields.

Three of them were also students.

Each of our clients had been caught with between 2 and 9 ecstasy pills.

One of those clients received two drug possession charges as he was caught with 7 ecstasy pills and a little over 1 gram of cocaine.

All of our clients wished to plead guilty and our expert drug defence lawyers represented them at each court date, as well as the final sentencing hearing.

As always, our lawyers spent considerable amounts of time working on each case and preparing compelling sentencing submissions which emphasised the need for a lenient penalty.

Despite the fact that some of our clients were caught with numerous pills, our outstanding advocates were able to persuade the magistrate in Burwood Local Court to impose section 10s in every case.

This means that while the court accepted their guilty pleas, the offence was not recorded on their criminal records.

Our clients therefore avoided the negative consequences which can flow from having a criminal record.

In Campbelltown Local Court, Sydney Criminal Lawyers® successfully obtained bail for a 23 year old ‘repeat offender’ who was advised by his former solicitors and barrister that he had no chance of getting bail.

The man has several previous convictions for robbery, larceny, drugs and break & enter offences.

Most significantly, he was already on strict conditional bail including a night-time curfew for ‘aggravated break, enter & steal’ at the time of his present charges.

His present charges involve him allegedly ‘break & entering’ a home, stealing credit cards and using those cards shortly thereafter to make purchases at 2 nearby petrol stations and a convenience store, at a time when he was supposed to be home for his curfew.

According to the police ‘facts’, his use of the stolen cards is captured on CCTV footage and he had was in possession of receipts from the purchases when arrested.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained bail despite all of those factors.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® obtained ‘Suspended Sentences’ (no prison) in Downing Centre District Court for our 22 year old client for ‘Supply Drug on Ongoing Basis’, 11 charges of ‘Supply Prohibited Drug’ and ‘Participate in Criminal Group’.

The case involved the supply of approximately 60 ounces of heroin and cocaine over several months.

Our Ugur Nedim persuasively presented the case before the Downing Centre District Court Judge who ultimately found exceptional circumstances in our client’s favour and refrained from sending him to prison.

All involved had expected a lengthy prison sentence.

It is an incredible result considering that our client has several previous criminal convictions, and the official sentencing statistics for similar offenders say that 100% were sent to prison.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® convinced the DPP to withdraw two charges of ‘drug supply’ against our 20 year old Menai client, then obtained a ‘section 10 dismissal’ in Downing Centre Local Court for the remaining charge of ‘drug possession’.

This means that our client has no criminal convictions and is free to pursue her chosen career as a social worker without having to disclose a drug conviction.

The Presiding Magistrate in Hornsby Local Court dismissed drug possession charges against our 21 year old client from Wahroonga who was stopped and searched in a Pennant Hills carpark.

Police approached our client claiming he appeared to be ‘acting suspiciously’ by standing outside his car with a friend in an unlit area.

As usual, police alleged that our client appeared ‘nervous’ and ‘agitated’ and that he could not adequately explain why he was there.

They searched him and found 4 ecstacy tablets and a small amount of cannabis in resealable bags in his pocket.

The Magistrate found that this was not enough to ground a ‘suspicion on reasonable grounds’ and ruled the search to be illegal.

The evidence was then excluded and both charges were dismissed.

The Magistrate in Downing Centre Local Court dismissed the case against our 30 year old client who was charged with ‘resisting officer in execution of duty’.

Police arrested our client in Woolloomoolloo when they suspected him of possessing drugs.

Our client ‘violently resisted’ and was thrown to the footpath head-first, sustaining bruising to the face.

He was held face-down by police ‘for at least 2 minutes’.

The Magistrate found our client ‘not guilty’ and criticised police for acting ‘recklessly and outside their powers’.

Here are some recent examples of our criminal defence team getting charges dismissed due to mental health under ‘section 32:

The Magistrate in Ryde Local Court dismissed charges of larceny against our 37 year old client who was caught stealing a trolley-load of goods from Myer. The case was persuasively argued by Mr Nedim and the Magistrate stated ‘this is only the second section 32 that I have granted out of about 20 since I came to Ryde in April’.

Downing Centre Local Court dismissed charges of Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm and Common Assault against our 24 year old client despite it being his second assault case within 2 years. He received a criminal conviction for his previous case after his lawyers failed to inform him that his mental condition could be used to have his case dismissed.

Parramatta Local Court dismissed drug possession charges against our 33 year old client who was caught with 9 ecstacy tablets in his pocket. He was initially charged with ‘supply’ but Sydney Criminal Lawyers® had that charge withdrawn. The court found that there was a link between our client’s underlying depression and his use of drugs, and that the proposed treatment plan was adequate.

Wagga Wagga Local Court dismissed a charge of ‘use carriage service to make hoax threat’ against our 45 year old client who contacted the NSW Fire Service advising that a bomb had been placed at a fire station. The court found a significant link between our client’s post traumatic stress and his actions.

Our Senior Criminal Lawyers persuasively argued each of the cases in court.

Our 37 year old client was initially charged with ‘strictly indictable’ offences of ‘cultivate by enhanced indoor means prohibited plant for commercial purpose’ for growing 14 large cannabis plants under 4 tents in his Camperdown apartment and with supplying ecstacy.

He was also charged with several other offences involving selling fake goods and possessing prescribed restricted substances.

He was told by 2 other Sydney criminal law firms that:

He then came to Sydney Criminal Lawyers® who fought and succeeded in:

It pays to have a confident and superior defence team on your side.

The Presiding Magistrate in Downing Centre Local Court dismissed charges of ‘drug possession‘ against our 29 year old client after police searched his car illegally.

Our client was pulled over after he allegedly exceeded the speed limit and drove ‘recklessly’.

Police claimed that, when approached, he appeared ‘nervous’,’ fidgety’ and was ‘sweating profusely’.

Police then undertook a background check which showed that our client has a previous drug conviction.

His car was then searched and police found a plastic bag containing 58 grams of cannabis under the passenger seat.

The Magistrate accepted that our client’s nervousness was natural in the circumstances and that a previous drug conviction is not sufficient to justify a search.

The search was found to be illegal and the evidence of drugs was excluded.

The prosecution had no further evidence and the case was dismissed.

The Magistrate in Downing Centre Local Court was persuaded to discharge our 24 year old client without recording a criminal conviction against him despite being found in possession of 8 tablets of MDMA (‘ecstacy’).

Police approached our client in a Sydney Night Club after receiving information that he was selling ‘ecstacy’ tablets to patrons.

They asked whether he was in possession of drugs and he immediately produced a small resealable plastic bag containing 8 pills.

He was arrested and charged with ‘drug supply’ and ‘drug possession’.

The ‘drug supply’ charge was based on the law about ‘deemed supply’ – which says that a person can be charged with drug supply simply because they possess more than the ‘trafficable quantity’ of drugs eg more than 0.75 grams of ecstacy.

Our defence team wrote a detailed letter to Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (‘DPP’) which resulted in the ‘supply’ charge being withdrawn.

Our client then pleaded guilty to ‘possession’ and our Mr Nedim convinced the Magistrate to allow him to remain ‘conviction-free’ on the basis that a criminal conviction could have impacted upon his ability to become an accountant after completing his university studies.

All charges were withdrawn and dismissed in Downing Centre Local Court for our 30 year old client from Italy after the analysis of the alleged prohibited drugs came back negative.

Police observed our client approaching several people and selling capsules to patrons at the ‘AVIICI’ concert at Centennial Parklands, Sydney.

They searched him and located 73 tablets and capsules resembling ‘ecstacy’ in 4 separate resealable bags. They also found $770 cash on him.

He was then charged with ‘supply prohibited drug‘ and ‘deal with property suspected of being proceeds of crime’.

The substances were then analysed and found to be a legal drug known as ‘Lofton’.

It is important to note that the law says a person is guilty of drug supply even if they supply tablets that contain no drugs at all, as long as they sell them as if they were drugs.

Despite this, our defence team persuaded the prosecution to withdraw all charges on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to prove that our client was selling the substances as illegal drugs.

All drug charges have been dropped after our defence lawyers successfully argued that the prosecution evidence against our client was not strong enough to go to a jury trial.

Our client is a 42 year old man from Waterloo who was suspected of being part of a criminal syndicate that supplied drugs including heroin and ‘ecstacy’ from at least early 2013.

Police set up a surveillance operation in May 2013 that intercepted phone calls between our client and others allegedly involved in that syndicate.

Those intercepts allegedly established that our client was a ‘drug runner’ who sold drugs on behalf of those higher in the syndicate.

Video surveillance also allegedly captured him selling drugs on at least two occasions.

Our client and two other syndicate members were later arrested and charged with various drug offences – our client was charged with supplying heroin on 10th and 31st July 2013.

After several months of intense fighting, our Senior Criminal Defence Team was able to convince the prosecution that the evidence was insufficient to prove the charges against our client beyond reasonable doubt.

All charges against him were then withdrawn.

The two ‘co-accused’ are represented by other criminal law firms who have not been able to have their clients’ cases dropped.

Those clients are now facing an expensive, lengthy and risky District Court trial unless they plead guilty to their charges.

In Downing Centre District Court, our 24 year old client from Rydalmere was given a ‘section 10 bond’ despite pleading guilty to supplying 16 ecstacy tablets and possessing amphetamines.

This means that she avoids a criminal conviction altogether.

She is a Project Analyst with a Sydney-based telecommunications company that contracts to various government organisations.

She attended the Stereosonic Music Festival, Olympic Park where police allegedly saw her selling tablets to other party-goers.

Police approached and saw her holding a condom containing what appeared to be tablets and capsules.

They immediately cautioned her, seized the pills and placed her under arrest.

She then made a range of admissions and was charged with one count of ‘drug supply‘ and two counts of ‘drug possession’.

The ecstacy (or ‘MDMA’) tablets weighed a total of 5.44 grams. A capsule of amphetamines was also found.

The quantity of drugs made it a ‘strictly indictable case’ which means that it had to go to the District Court.

It was a strong case of ‘actual supply’.

However, Sydney Drug Lawyers persuaded the prosecution to significantly amend the ‘facts’ and to treat the matter as a ‘deemed supply’ only, which meant that it was less-serious.

Our client then pleaded guilty to one charge of ‘deemed supply’.

She placed herself in the best possible position before her sentencing date by attending counselling and gathering character references.

A counselling letter was obtained and our defence team successfully persuaded the District Court Judge to keep her conviction-free.

This means that the incident is unlikely to affect our client’s current job or her future career prospects.

Two young men and one young woman who pleaded ‘guilty’ in Deniliquin Local Court to numerous charges of ‘drug possession’ have had their convictions overturned on appeal to Downing Centre District Court.

The charges arose after police applied for a Drug Dog Detection Warrant for the detection of drugs in cars travelling through NSW towards the Con/Fest Music Festival in the A.C.T.

Police pulled over our client’s car which contained two passengers, and the drug detection dog indicated the presence of drugs.

The driver agreed to a search and police located 5.5 grams of liquid LSD, one sugar cube of LSD, 4 MDMA (‘ecstacy’) tablets and 2 grams of cannabis.

All three occupants participated in police interviews and admitted that they possessed the drugs for personal use.

Two of them were charged with 2 counts of ‘drug possession‘ for the ecstacy and LSD. The third was additionally charged with cannabis possession.

All were later convicted of all charges in Deniliquin Local Court and given criminal convictions and fines.

Our firm did not represent them in the Local Court.

One of them later contacted our firm and we immediately lodged an appeal against the severity of his sentences.

The remaining two contacted our firm shortly thereafter and we also lodged appeals for them.

For strategic reasons, we arranged for all of the cases to be transferred to Downing Centre District Court.

Despite the number of different drugs and multiple charges, our Senior Criminal Lawyer Mitchell Cavanagh persuaded the Judge to overturn all of the convictions by ordering ‘section 10 good behaviour bonds’.

This means that all of our clients remain conviction-free. The fines were also overturned.

During the Appeal, Mr Cavanagh directed His Honour to a binding decision of the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal which states that a court may deal with a person without conviction despite the presence of substantial quantities of drugs and numerous charges.

That decision also says that:

1. A ‘section 10’ (non-conviction) can even be awarded in cases of drug supply, including cases where there are 20 or more ecstacy tablets,

2. A good behaviour bond without conviction is a significant penalty in itself, and

3. Whether or not a conviction is recorded makes little difference to whether the penalty is adequate or inadequate.

Once again, our firm’s superior legal knowledge, thorough preparation and persuasive presentation has made a significant difference to result achieved.

Our 21 year old client was charged with drug supply after police observed him smoking crystal methylamphetamine (‘ice’) through a glass pipe in the driver seat of his car.

Police searched the car and located more ‘ice’ in a small resealable bag, 6 tablets of MDMA (‘ecstacy’), drug paraphernalia and a quantity of cash.

They charged him with drug supply due to the quantity of drugs found – this charge is also known as ‘deemed drug supply’.

Once again, our defence team wrote a detailed letter to police requesting withdrawal of the drug supply charges on the basis that our client pleads guilty to the less-serious charge of ‘drug possession’.

The request was successful and our client then pleaded guilty to drug possession.

Our client was represented in court by our senior lawyers who persuaded the Magistrate in Downing Centre Local Court to award our client a ‘section 10’ which means that he avoids a criminal conviction altogether.

Our 26 year old client was charged with supplying 2.4 grams of cocaine, and a ‘backup’ charge of drug possession, after police located drugs and drug paraphernalia including electronic scales and resealable bags in a kitchen cupboard at his one-bedroom unit in Paddington.

Our client was the sole lessee of the unit, although his girlfriend also lived there and friends also attended for social gatherings.

The prosecution case failed because they could not prove beyond reasonable doubt that our client ‘exclusively possessed’ the drugs, to the exclusion of all others.

In drug cases, police must prove ‘exclusive possession’- in other words, police must exclude any reasonable possibility that the drugs belonged to someone else.

In this case, our lawyers ensured that ample evidence came before the court that the drugs could have belonged to our client’s partner or any one of a number of people who recently attended the unit.

The Magistrate in Downing Centre Local Court therefore found our client ‘not guilty’ and dismissed both of the charges.

The Harbourlife Music Festival on 8th November 2014 led to a large number of arrests for drug possession.

On 5th December, our Senior Lawyers each represented 3 clients who pleaded guilty to drug possession in Downing Centre Local Court.

Our clients were from a range of economic, cultural and employment backgrounds – including students, retail worker, tradespersons and professionals in upper management.

ALL of our clients escaped criminal records after our lawyers persuaded the Magistrate to grant them ‘section 10s’ – which means guilty but no criminal conviction.

They are free to get on with their lives without the complications of a criminal record.

Our client is a 26 year old Columbian national who, before his arrest, was in Australia on a student visa.

He is charged with importing 63 kilograms of methamphetamine from Mexico and Columbia into Australia, in contravention of section 307.1 of the Criminal Code Act.

The offence carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

The shipment was detected through telephone intercepts and physical surveillance, and the drugs were intercepted by the AFP in Sydney and replaced with an innocuous substance that was found in the boot of a car in Burwood.

It is alleged that our client was involved in the importation and that the case against him is strong.

The Bail Act 2013 requires the court to consider a range of factors when deciding to release a person from custody.

Those factors include: the seriousness of the charge, the strength of the prosecution case, the person’s links to the community, the risk of not turning up to court, the risk of reoffending, the time they would spend in prison if not granted bail and the need to be free to prepare for their case.

Our client was in a difficult position due to the seriousness and alleged strength of the case, his minimal links to the community and the consequent risk of failing to attend court.

However, our defence team prepared detailed written submissions to the court focusing upon (1) prosecution delays in serving evidence, (2) the fact that he would be spending a significant amount of time behind bars awaiting trial, and (3) our need to have him free to assist in the preparation of his defence.

The prosecution strongly opposed bail, and prepared it’s own written submissions.

However, the Magistrate in Central Local Court ultimately acceded to our request and granted conditional bail to our client.

The next step will be for our experienced team to use our vast specialised experience in commercial drug cases to secure him the optimal outcome.

In Burwood Local Court, each of our Senior Lawyers represented 3 clients who were caught possessing drugs at the Stereosonic Music Festival.

Our clients were from various social, economic and cultural backgrounds and worked in a range of fields – from retail, to accountant, to company executive, to business owner.

Three of our clients were also students.

Most were caught for possessing MDMA tablets, also known as ‘ecstacy’ – ranging from 2 to 9 pills. One of our clients had two ‘drug possession’ charges against him for possessing 7 ecstacy tablets and just over 1 gram of cocaine.

All of our clients’ cases were thoroughly prepared and persuasively presented in court.

This resulted in the Magistrate allowing all of them to avoid criminal records by granting them ‘Section 10s’.

Section 10 means that, even though a person is guilty, a criminal conviction is not recorded against their name.

Our clients are free to get on with their lives without the burden of a criminal record.

In May 2013, our client pleaded guilty to Supplying a Commercial Quantity of Prohibited Drug and 3 counts of Possess Prohibited Drug.

He was given a two-year ‘Suspended Sentence’ and 3 x three-year ‘Section 9 Good Behaviour Bonds’ for those charges by the Presiding Judge in Downing Centre District Court. This was an excellent result given the seriousness of the charges.

However, in November 2014, he was found in possession of MDMA (‘ecstacy’) tablets and a quantity of cannabis, and charged with two counts of drug possession. Those charges caused him to breach his ‘Suspended Sentence’ and his ‘Good Behaviour Bonds’.

In the lead-up to his court proceedings, our legal team gathered material supporting the assertion that our client had taken significant steps towards rehabilitation, but had found it difficult at times and relapsed.

In the result, the Presiding Judge was persuaded that there were good reasons to excuse the breach of Suspended Sentence. The breach was therefore excused and our client was given a fresh two-year section 9 good behaviour bond.

He therefore avoids prison and can continue in his efforts towards rehabilitation.

Our 23 year old client has been granted conditional bail in Central Local Court after being charged with ‘supplying a large commercial quantity of prohibited drug’ and ‘knowingly participate in criminal group’.

Police conducted a controlled operation into the alleged production and supply of methylamphetamine originating out of a clandestine laboratory in Ryde, NSW.

Police used surveillance devices and physical monitoring to track the movement of substances from that location to other parts of Sydney.

Our client was arrested together with four other young men who were allegedly in possession of 2.4 kilograms of methylamphetamine.

It is additionally alleged that our client is captured on surveillance footage handling the packages within which the drugs were found.

All five defendants then came before the Presiding Magistrate in Central Local Court.

They all faced an uphill battle when it came to bail because ‘large commercial drug supply’ is one of the offences captured by the new “show cause” provisions of the Bail Act – which means that it is very difficult to obtain bail in such cases.

However, our senior lawyers made extensive verbal submissions which ultimately convinced the Magistrate to grant bail to our client.

All of the other four other defendants were refused bail.

It is just another example of how superior legal representation can make all the difference when it comes to your liberty.

Our client is a 58-year-old lady who owns a tobacconist store in the CBD.

Police had previously seized synthetic drugs from her store, and had received further reports that synthetic cannabis was still being sold.

They obtained a warrant to search the premises and were able to locate various forms of synthetic cannabis, with an estimated value of $10,000.

Our client was then charged with ‘deemed supply’, which means that she was alleged to have more than the ‘traffickable’ quantity of drugs in her possession for the purpose of supply. A ‘deemed supply’ charge can be brought even if there is no evidence that the person actually supplied any drugs.

The laws relating to the sale of synthetic cannabis were changing at the time, and the act of supplying synthetic cannabis had only become an offence 10 days before our client was charged.

Our lawyers were able to persuade the prosecution to drop the charges on that basis, meaning that our client is spared the expense, stress and anxiety of having to fight the case in court.

Our three clients are all Indonesian nationals who were crew members aboard a ship headed for Australia.

The ship’s cargo-hold was altered to increase its capacity, containing a speed boat and dozens of ‘Prada’ bags filled with a total of over 600 kilograms of heroin.

The ship anchored approximately two kilometres from Australian shores, and the speedboat was ferried back and forth unloading the heroin-filled bags onto the mainland.

Unknown to the ship’s captain and crew, Australian authorities had been monitoring the operation and ultimately arrested all on board the ship.

The captain and officers were all convicted at trial. They were represented by other lawyers.

Six crew members faced a separate trial, with our team representing three of the men in Downing Centre District Court.

We advised our clients not to give evidence after the close of the prosecution case at trial, as the state of the evidence was that knowledge or recklessness had not been proved beyond reasonable doubt. They were ultimately found ‘not guilty’ of all charges.

The remaining three crew members – represented by other lawyers – each testified in court. They were questioned at length and ultimately found guilty. In our view, it was a significant strategic error to have exposed the men to cross-examination, given the weaknesses in the evidence at the close of the prosecution case.

Our client is a 27-year-old apprentice plumber from Sydney.

Police observed him walking along a footpath with another person outside a popular annual music festival. As our client was adjusting his pants, a single brown pill fell out of his pocket onto the ground. Police saw this, approached and showed him identification. Our client then handed the pill to police, admitting it was ‘ecstacy’.

Police asked whether he had any other pills, and our client produced a bag containing another five ecstasy pills. Police then searched him and found another bag containing 6 more ecstasy pills. He made admissions to police that he was going to give some of the pills to his girlfriend and friends, which amounts to ‘drug supply’ under the law.

In total, our client was found with 12 ecstasy pills. As this is well above the ‘trafficable quantity’ of 0.75 grams – and the fact our client admitted intending to supply pills to others – our client was charged with ‘deemed supply’, which means he was taken to have the drugs upon him for the purpose of supply.

Our client pleaded guilty in the Local Court and, because the quantity was also above the ‘strictly indictable’ weight of 1.25 grams, the case proceeded to the District Court.

Our client told us he saw several criminal lawyers who each advised him that it was not possible to avoid a criminal conviction for a ‘deemed supply’ for so many ecstacy pills. In our view, that advice was contrary to several authorities in the NSWCCA and District Court which make it clear that higher courts can, and indeed have, exercised discretion under section 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 not to record a criminal conviction for the supply of several ecstacy tablets (see especially R v Mauger).

We assisted our client to prepare a range of favourable materials, including character references, a letter of apology and evidence that he may lose his job upon receiving a criminal record.

In the District Court, the prosecutor presented several cases which state that a prison sentence is appropriate in circumstances similar to that of our client.

In addition to the subjective materials, we presented cases to the contrary and argued at length that it was appropriate for the court to deal with our client by way of a section 10 good behaviour bond.

In the result, the Judge was persuaded to exercise her discretion and place our client on an 18-month bond without recording a criminal conviction against him.

He looks forward to continuing his career and establishing his own business in the future.

Our client is a 38-year-old teacher.

Police in plain clothes observed him stand up and exit a bar as they were entering the premises with a drug-detection dog.

Police decided to approach him, at which time our client immediately produced a small bag of cocaine and handed it over to them.

Police then arrested and issued him with a court attendance notice.

It wasn’t the first time our client was in trouble for drug possession.

He had two prior drug possession offences, and was placed each time on a ‘section 10’ good behaviour bond, without a criminal conviction.

He had been warned by the magistrate on the previous occasion that such leniency would not be extended to him on a third occasion.

Despite that warning, our lawyers ensured he was placed in the best possible position in court. We assisted him to prepare character references, a letter of apology and evidence he would likely lose the job he recently acquired if convicted.

Our client also made enquiries about participating in a drug rehabilitation program, and we produced evidence of his efforts to the court.

We then made extensive submissions before the court, and with some hesitation the magistrate was ultimately persuaded to deal with our client by placing him on a good behaviour bond without conviction once again.

Our client is a foreign national on a working holiday visa.

A few months into her stay in Australia, she decided to attend a music festival with a group of friends.

On the day of the festival, she was pressured to carry 14 MDMA (‘ecstacy’) tablets into the festival grounds.

The male members of the group, including her boyfriend at the time, felt that as a female she would come under the least suspicion from security and police, who were checking for illegal drugs at the festival entry.

A sniffer dog gave a positive indication and our client quickly admitted to possessing the tablets.

She was then arrested and charged with ‘drug supply’ due to the number of tablets found. In that regard, the law provides that a person found with more than the ‘trafficable quantity’ of drugs can be charged with supply. This is known as ‘deemed supply’. The trafficable quantity of MDMA is just 0.75 grams.

If a person is charged with deemed supply, the onus of proof then shifts to them to prove ‘on the balance of probabilities’ that they were in possession of the drugs for the purpose of something other than supply.

The law also provides that a person who holds drugs momentarily for the owner with a view to returning it is not guilty of supply.

An issue for our client was that there were a number of people to whom the drugs were to be distributed upon entry to the festival, and she made admissions to police that she intended to supply the tablets to these people.

Despite the issues, our defence team wrote a detailed letter – known as ‘representations’ formally requesting withdrawal of the supply charge provided that our client pleaded guilty to drug possession.

She pleaded guilty to that lesser charge and we assisted her in gathering a range of subjective materials, including documents in relation to the impact of a criminal conviction.

After extensive verbal submissions in the local court, and despite submissions against a ‘non conviction’ by the prosecution, Her Honour was persuaded to impose a two-year good behaviour bond without a criminal conviction.

This is an excellent result given the number of tablets involved.

Our client is a 25 year old man who works in the marketing industry.

Police were conducting patrols outside a popular music festival with the assistance of their drug detection dogs, when a dog indicated the presence of drugs in our client’s possession.

When asked by police as to whether he had any drugs on him, our client immediately made full admissions and produced a small resealable bag containing 7 MDMA (‘ecstacy’) pills.

Under the law, any amount of ‘ecstasy’ above 0.75g is considered to be in a person’s possession for the purpose of supply. Our client was not charged with supply on this occasion, but with drug possession only.

Our client instructed us that he intended to plead guilty to that charge, which was the appropriate plea given his immediate admissions and the finding of drugs.

We assisting him in preparing his letter of apology to the court, in seeing a counsellor and obtaining a letter of attendance from her, and in gathering character references with the relevant content.

We made extensive submissions in court in relation to his acceptance of responsibility, steps towards addressing underlying issues, remorse and the likely impact of a criminal conviction on his future plans.

With some hesitation, Her Honour was ultimately persuaded not to record a conviction against our client’s name, but rather to place him on an 18-month good behaviour bond without a criminal record.

Our client was overjoyed by the outcome and looks forward to continuing to advance in his career.

Our client is a 24 year old physical education student.

Police say they observed him entering a ‘known drug premises’ and exiting a short time later with a package.

They followed his car and pulled him over a short time later. They asked whether he had any drugs in the car, to which he replied ‘some steroids’.

They then search his car, located the package on the passenger seat, and within it found a total of 800 Dianabol (steroid) tablets, a 10 ml vial of Sustanox X250 (a steroid) and approximately 1 gram of cannabis.

Our client was then charged with three counts of drug possession in respect of the substances. Given the state of the evidence and our client’s admissions, and after some alterations were agreed by the prosecution to the ‘full facts’, pleas of guilty were entered to the charges.

Our client instructed that he was “obsessed” with his body image. Accordingly, we arranged for him to see a psychologist, who diagnosed him with ‘body dysmorphia’.

He continued seeing the psychologist in the lead-up to the sentencing hearing, and we obtained a report about his underlying issues and the steps he taken towards address them.

We also assisting him to prepare a letter to the court which outlined his acceptance of responsibility, his remorse and his efforts towards rehabilitation. We also helped him in obtaining character references in the proper form.

Despite the quantity of drugs and number of charges, we ultimately persuaded the magistrate to place him on good behaviour bonds for a period of two-years without recording a criminal conviction against his name.

Our previously-anxious client is now confident that his studies will lead to employment as a teacher or instructor.

If you were walking to work and saw a stranger shooting up heroin, what would you do?

If you’re like most people, you’d probably ignore them and keep going. If you were feeling particularly Samaritan, you might even stop and make sure they’re ok.

Unfortunately, the journalists of The Daily Telegraph aren’t like most people. Instead, it seems their natural reaction is to pull out their camera, take a photo, and use it in yet another scare campaign against drug users.

Indeed, this is what happened last Friday when the paper published a photo on its front page of a man shooting up in Surry Hills, with the headline: “A Shot In The Heart”.

It’s quite a confronting image. Heroin is a potentially dangerous drug – it’s highly addictive and many of us know someone who has had their life adversely affected through its use. And perhaps it’s normal to be concerned about its use in our neighbourhoods, or near our families.

However, twenty years of scaremongering for harsher drug possession penalties hasn’t helped overcome the issue of drugs. And for us to have a sensible conversation about the way forward, headlines like this are not helpful.

Dr Marianne Jauncey, medical director at the Kings Cross Supervised Injecting Centre, recently told reporters that clients that are distressed about the tabloid newspaper’s treatment of the issue. The doctor is particularly worried that such portrayals could prevent drug users from seeking help.

“There’s very much an issue about continuing to demonise (problem drug users), as it doesn’t help anybody. All of us want to fix it, no matter what side of the debate you’re on. All of us want less problem drug use, but emotions and morals can get in the way,” Dr Jauncey remarked.

She believes the effect of reporting like this, and calls for harsher drug possession penalties generally, is that habitual users are less likely to come forward and get the assistance they need.

“We all want them to get better and have the courage to seek help. Stories like this have the exact opposite effect that everybody would want. When you splash their face all over the front page of the paper, people become vulnerable, upset and tend to turn inwards. Why on earth would you say yes, I’m like that person? It absolutely further stigmatises people who are users and (makes them) less likely to seek help.”

The Press Council agrees. Under its guidelines, publications should “avoid causing or contributing materially to substantial offence, distress or prejudice, or a substantial risk to health or safety, unless doing so is sufficiently in the public interest”.

Those like Dr Jaucey know all-to-well that this guidance hasn’t stopped the tabloids in the past. The Supervised Injecting Centre is one of the few victories achieved by harm reduction advocates in recent times, but it came with a struggle. Although the centre was opened in 2001, it took almost 10 years for it to gain permanent approval – no thanks to tabloids and radio shock jocks stoking opposition to it.

“It’s been said before, but it needs to be said again and again until it is done – this place needs to be shut down now,” published The Daily Telegraph in 2006. That headline was accompanied by photographs of around 100 “potentially deadly blood-tainted needles” dumped near the clinic, inferring that this was a consequence of having the centre there.

There was just one problem, the claims were untrue. Although someone had dumped the needles there, there was no evidence they had come from the injecting centre. In fact, the evidence was to the contrary.

“They were most certainly not syringes used by drug users.” Dr van Beek, former head of the Centre, said at the time “They were also not the brand of syringes distributed in this area.”

These inconsistencies did not stop critics of drug reform from the exploiting the report. Later that day, former-opposition leader Peter Debnam called a press conference arguing for the closure of the centre, and assuring that “… no other injecting rooms will be opened up in any other suburbs.”

A decade later, we now know the centre has been a resounding success, especially when compared to the effects of harsher drug possession penalties.

The annual cost of the Injecting Centre is about $3 million, roughly equivalent to the annual cost of imprisoning 30 people. While the benefits of incarceration are questionable at best, the Injecting Centre produces larger financial savings than it costs to run – while fears of increased crime and usage have been disproven.

“Harm-reduction approaches can only work if governments and policymakers alike recognise the complexity of the “drug problem”. No single solution exists for all kinds of drug users, or all kinds of drug use.” writes Gideon Lasco, a drug policy expert at the University of Amsterdam.

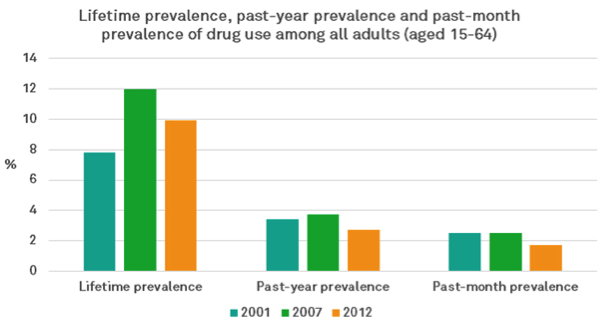

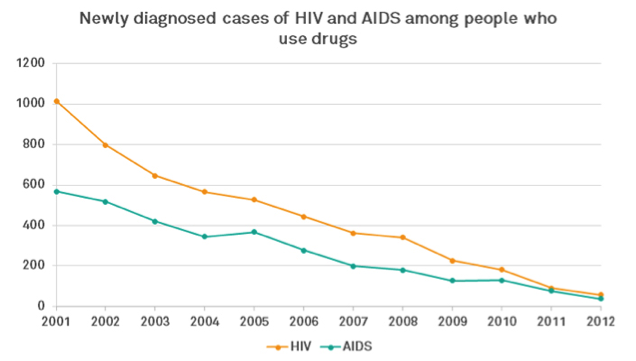

Mr Lasco uses Portugal to demonstrate his point. In 2001, the nation bought in new

drug possession reforms that see drug users sent to three-person local committees, rather than handed a criminal conviction, if they’re found in possession of small quantities of drugs.

These committees consider a range of interventions depending on the person before them. Many are encouraged to seek treatment, while others may be handed a fine to discourage further use.

Ten years on, drug use rates have not increased, while drug-related deaths, as well as problematic and adolescent drug use, have decreased.

This is the kind of sensible, evidence-based approach is hard to ignore. However achieving sensible reform is made more difficult while tabloids sensationalise the issue of drugs, and demonise drug users.

In a landmark decision, Australian federal and state food ministers have agreed that hemp seed food will soon be legally available for consumption. The Australian and New Zealand Ministerial Forum on Food Regulation approved the move, at a Council of Australian Governments (COAG) meeting in Adelaide last Friday.

The decision comes in the wake of a Food Standards Australia and New Zealand meeting in March that gave the green light for the sale of foods derived from hemp seeds that are low in THC – the psychoactive component of the cannabis plant.

A communique released after the COAG meeting outlined that the ministers had received a Swinburne University of Technology report regarding the consumption of low-THC food and the effect they could have on roadside drug testing operations.

The report found that it “is highly unlikely” that the consumption of hemp seed food would result in any positive saliva, blood and urine tests. “In light of these findings ministers supported the draft standard that will allow low-THC hemp seeds to be sold as a food,” the communique reads.

The change is expected to come into effect in six months, in both Australia and New Zealand. A range of state and territory legislation that currently outlaw the sale of the food will need to be amended. This will open up the international hemp seed food market, which is estimated to be a billion dollar a year industry.

A globally accepted food

Up until last Friday, Australia and New Zealand were the only countries in the world where the consumption of hemp seed food was prohibited. Under standard 1.4.4 of the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code, all species of cannabis have been prohibited from being added to or sold as food.

Hemp seeds are produced by the hemp plant, which is low in THC. While both marijuana and hemp are strains of Cannabis sativa, hemp has been specifically cultivated to produce industrial fibre, oils and seeds. You can smoke hemp till the cows come home, and it won’t get you high.

Hemp seed foods are widely available throughout Europe and North America. In the States, the consumption of hemp food is legal but the production is not. Australian producers see this as a lucrative market to step into.

Currently, China is the largest hemp seed producer in the world, followed by countries such as France, Canada, South Korea, the Netherlands and Chile.

A boom for the Australian hemp industry

Secretary of the Australian HEMP Party Andrew Kavasilas welcomes the long overdue decision. “I’ve been growing under hemp permits since 1999,” he said. “In NSW, it wasn’t until 2008 that we actually had a Hemp Act, but it was only related to fibre.”

Those in the Australian industry have been “itching” for the food to become legalise, Mr Kavasilas said. He’s also the founding director of Vitahemp Australia. “We’ve actually had to accelerate our plans on winter cropping,” he told Sydney Criminal Lawyers®. “We’ve got in excess of 30 hectares going.”

The Australian hemp industry has stagnated due to the ban on hemp foods, Kavasilas explained. He pointed to a 2013 Tasmanian government inquiry into the state’s industrial hemp industry, which found “the ban on hemp seed food was holding the entire industry back.”

The beneficial seed

Hemp seeds are said to be the most nutritionally complete food source in the world. They have a balance of omega 3 and 6, along with Iron, Vitamin E and all of the essential amino acids. They’re high in protein, and can be eaten whole, pressed as an oil or ground into a powder.

The seeds can produce a variety of different foods. They can be eaten as a grain as part of muesli or cereals. They can be used to produce non-dairy milk and ice cream. And they can be added to a wide variety of different meals to reap their nutritional benefits.

So then why are hemp seeds illegal in Australia?

Well according to Mr Kavasilas, unlike marijuana and its products, hemp was not prohibited under the various United Nations drug control conventions. It’s continued to be utilised in countries like India, China and Russia.

However, it was the United States that banned hemp in the early twentieth century. This was done amidst the “reefer madness” anti-marijuana hysteria of the time, and many believe it served the interests of big business to be rid of the versatile plant.

The US ban influenced other western nations to follow suit. So what we’re seeing now is the reintroduction of industrial hemp in the western world.

Roadside drug testing

The Australian hemp industry has been campaigning for hemp seed food to be legalised for decades. However, authorities have been hesitant to allow this to happen, over concerns the low-THC foods may interfere with the results of roadside drug testing programs.

The problem with roadside drug testing in Australia is that a positive reading can be registered for tiny traces of certain drugs in a driver’s system. Along with THC, police test for MDMA and amphetamines, via a saliva test.

When police carry out random breath testing for alcohol, they’re testing for levels of driver impairment – hence the categories of low, mid and high range drink driving. This is an approach based on research that’s shown certain levels of alcohol in a driver’s blood lead to increased risks when they’re behind the wheel of a car.

However, roadside drug testing does not test for impairment.

A grey area

As it was announced at the COAG meeting, the Swinburne University report said it was “highly unlikely” that someone who had been consuming hemp seed food would test positive for roadside drug testing.

But, there have been cases in the past where an individual has been charged with drug driving, and the driver has claimed that they hadn’t been smoking marijuana, but rather they’d been eating hemp seed products.

Mr Kavasilas agrees that it’s unlikely that traces of THC in hemp seed food would show up in police saliva tests. But he said that if it did happen to detect the traces, “it’s highly likely” that a supplementary laboratory test would show up positive.